You may have heard the term Irish Diaspora before, but what does it actually mean? In recent years, the term has become quite broad, but at its core, it refers to people of Irish ancestry who live outside of Ireland—whether they emigrated generations ago or are recent arrivals. It can also include those with distant roots to Ireland who feel connected to Irish culture and heritage. Depending on how you define it, the Irish Diaspora could encompass tens of millions of people around the world!

For this article, I’m focusing on Irish emigrants and their descendants, which brings the number down to the millions—making it a more manageable scope. As a reminder, I like to explore broad topics by providing a basic understanding, offering enough information to educate about different aspects of Ireland, including its history and culture. Each reason I mention for Irish emigration could easily be the subject of several books—it’s a complex and fascinating topic. What follows is just a brief overview of the Irish Diaspora.

The Irish government has refined the definition of the diaspora to include emigrants, their children, and grandchildren. This narrower focus reduces the number of people who fall under the term ‘Irish diaspora.’ Did you know that you can apply for Irish citizenship and get an Irish passport if you have Irish grandparents?

So, why are there so many Irish and their descendants living abroad? Since the 1700s, approximately 10 million people have emigrated from Ireland—more than Ireland’s current population today. What motivated so many Irish to leave, and where did they go?

The first thing to understand is that Ireland was a conquered country. England’s involvement began with the Anglo-Norman invasion in the 12th century. However, it was during the Tudor era, especially under Queen Elizabeth I, that English rule expanded significantly in the 16th century. (Someday, I might dive deeper into that history!) During this period, the English employed various strategies: military conquest (think Cromwell), colonization—bringing Protestant Scots to Northern Ireland and displacing Catholic Irish—and the imposition of English law, language, and religion. Much of this colonization left Ireland in deep poverty and fueled centuries of hardship and conflict.

Then came the Gorta Mór—the Great Hunger—in the mid-1840s. When the potato crop failed, millions of Irish people faced starvation. Sadly, England’s response was inadequate; instead of helping, they even sent food from Ireland to England. Families were evicted from their homes, left with nothing, and many consider the famine to be an act of genocide. Millions died, and millions more emigrated—Ireland’s population was halved, and the country is still in the process of recovery today. If you visit Ireland, you’ll see hundreds of abandoned homes, known as Famine Homes, scattered across the landscape as silent reminders of that tragedy.

Later, in the late 1800s, Ireland experienced the Land Wars. Irish tenants, unable to pay exorbitant rents and taxes, fought to defend their rights. This struggle continued until 1914. Imagine enduring the devastation of the famine only to face ongoing evictions and unpayable rents—an ongoing hardship that deeply shaped Irish history and resilience.

Next came the Irish War of Independence. The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) evolved into the Irish Republican Army (IRA), and from 1919 to 1921, they fought a guerrilla war to secure Irish self-rule. The outcome was the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922, while Northern Ireland remained part of the United Kingdom.

The 1960s and 1970s saw renewed activity with the IRA, as they fought for the rights of Northern Irish people within Britain’s legal system and, ultimately, for a united Ireland. This long struggle finally led to a peace agreement in 1998. Today, Northern Ireland remains part of Great Britain.

So, where did all the Irish go during these waves of emigration? Many headed to the United States, Australia, Great Britain—especially Liverpool—Canada, and even Argentina. These countries have long been popular destinations for Irish emigrants.

Just like in all countries, Ireland today experiences a steady flow of both emigration and immigration. An interesting note from the National Museum of Ireland is that, historically, emigration has involved a higher proportion of females, often young and single.

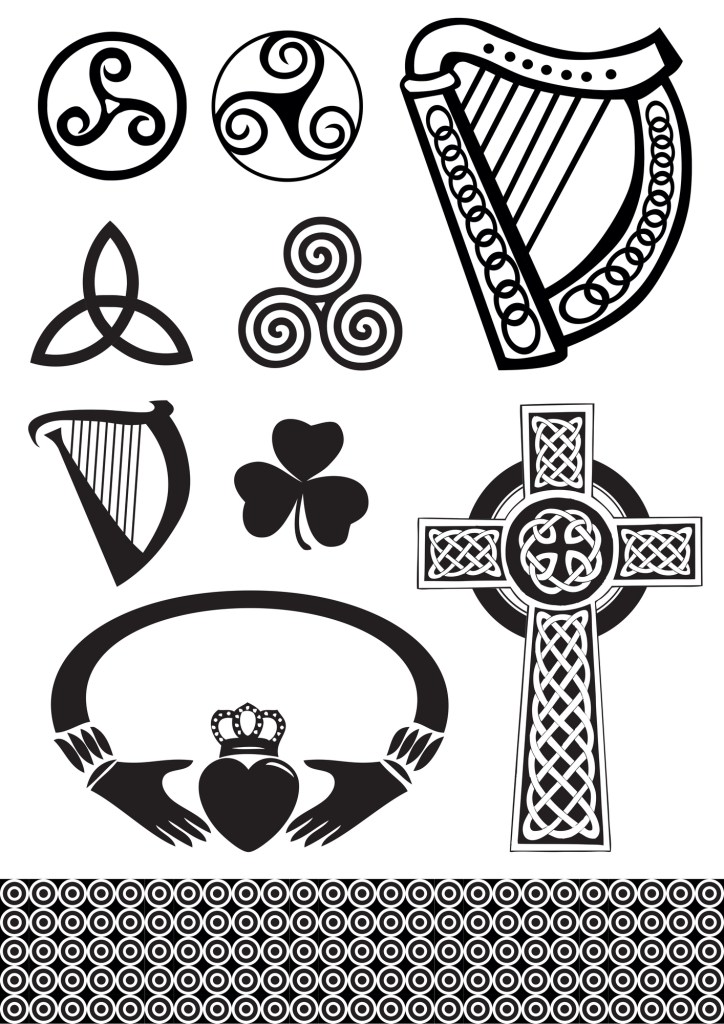

In my travels and even in teaching, I’ve noticed that people with Irish, Scottish, and Welsh heritage tend to be proud of their Celtic roots—they know they have Celtic blood and celebrate it.

There are countless songs, poems, and stories about the old country. I believe that because many Irish didn’t want to leave their homeland, they passed down that deep longing for home through generations, keeping the spirit of Ireland alive wherever their descendants now live.

Ireland actively works to connect with its diaspora, recognizing how important this link is to their culture, economy, and politics. Sean Fleming has been the Minister of State for Diaspora and Overseas Aid since 2014, a role dedicated to strengthening these international connections.

Additionally, genealogist societies are found in each county, helping people trace their Irish roots. There are also many online groups, especially on Facebook, created to connect people with Ireland and explore their Irish heritage.

Here’s some music to help sooth your longing:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vI0wTK1MIKs (lots of ballads) songs of Irish Immigration

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p6mgf7wMwE8 (Eddie Rabbit, who had Irish ancestry and who my mother used to babysit!)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=833Peu3J-fg (Elvis Presley, also claims Irish ancestry.)

Are you a part of this Irish Diaspora? My first Irish ancestors came over in the 1700s, then my great grandmothers in 1897/99. When did your ancestors leave the Emerald Isle? Do you know why they decided to leave?